|

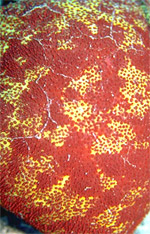

Each generation on top of the next: A coral "head" is formed of many individual polyps, each

polyp only a few millimeters in diameter. The colony of polyps function

essentially as a single organism by sharing nutrients via a well

developed gastrovascular network, and the polyps are clones, each

having the same genetic structure. Each polyp generation grows on

the skeletal Each generation on top of the next: A coral "head" is formed of many individual polyps, each

polyp only a few millimeters in diameter. The colony of polyps function

essentially as a single organism by sharing nutrients via a well

developed gastrovascular network, and the polyps are clones, each

having the same genetic structure. Each polyp generation grows on

the skeletal  remains of previous generations, forming a structure

that has a shape characteristic of the species, but subject to environmental

influences. remains of previous generations, forming a structure

that has a shape characteristic of the species, but subject to environmental

influences.

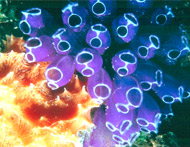

Usually growing close to the surface: Although sea anemones can catch fish

and other prey items and corals can catch plankton, they obtain

much of their nutrient requirement from symbiotic unicellular dinoflagellates

(type of algae) called zooxanthellae. Consequently, they are dependent

upon growing in sunlight and for that reason usually found not far

beneath the surface, although in clear waters corals can grow at

depths of 60 m (200 ft). Other corals, notably the cold-water genus

Lophelia, do not have associated algae, and can live in much deeper

water, with recent finds as deep as 3000 m. Corals breed by spawning,

with many corals of the same species in a region releasing gametes

simultaneously over a period of one to several nights around a full

moon.

Important for the reefs: Corals are major contributors to the physical structure of coral

reefs that develop only in tropical and subtropical waters. Some

corals exist in cold waters, such as off the coast of Norway (north

to at least 69° 14.24' N) and the Darwin Mounds off western

Scotland. The most extensive development of extant coral reef is

the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Queensland, Australia. Indonesia

is home to 581 of the world's 793 known coral reef-building coral

species. Important for the reefs: Corals are major contributors to the physical structure of coral

reefs that develop only in tropical and subtropical waters. Some

corals exist in cold waters, such as off the coast of Norway (north

to at least 69° 14.24' N) and the Darwin Mounds off western

Scotland. The most extensive development of extant coral reef is

the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Queensland, Australia. Indonesia

is home to 581 of the world's 793 known coral reef-building coral

species.

Great structures in the midst of sedimentary rocks: At certain times in the geological past corals were very abundant,

just as modern corals are in the warm clear tropical waters of certain

parts of the world today. And like modern corals their fossil ancestors

built reefs beneath the ancient seas. Some of these reefs now lie

as great structures in the midst of sedimentary rocks. Such reefs

can be found in the rocks of many parts of the world including those

of the Ordovician period of Vermont, the Silurian period of the

Michigan Basin and in many parts of Europe, the Devonian period

of Canada and the Ardennes in Belgium, and the Cretaceous period

of South America and Denmark. Reefs from both the Silurian and Carboniferous

periods have been recorded as far north as Siberia, and as far south

as Australia. Great structures in the midst of sedimentary rocks: At certain times in the geological past corals were very abundant,

just as modern corals are in the warm clear tropical waters of certain

parts of the world today. And like modern corals their fossil ancestors

built reefs beneath the ancient seas. Some of these reefs now lie

as great structures in the midst of sedimentary rocks. Such reefs

can be found in the rocks of many parts of the world including those

of the Ordovician period of Vermont, the Silurian period of the

Michigan Basin and in many parts of Europe, the Devonian period

of Canada and the Ardennes in Belgium, and the Cretaceous period

of South America and Denmark. Reefs from both the Silurian and Carboniferous

periods have been recorded as far north as Siberia, and as far south

as Australia.

Corals plus algae, plus sponges plus... However, these ancient reefs are not composed entirely of corals.

Algae and sponges, as well as the fossilized remains of many echinoids,

brachiopods, bivalves, gastropods, and trilobites that lived on

the reefs help to build them. These fossil reefs are prime locations

to look for fossils of many different types, besides the corals

themselves. Corals plus algae, plus sponges plus... However, these ancient reefs are not composed entirely of corals.

Algae and sponges, as well as the fossilized remains of many echinoids,

brachiopods, bivalves, gastropods, and trilobites that lived on

the reefs help to build them. These fossil reefs are prime locations

to look for fossils of many different types, besides the corals

themselves.

Solitary corals: Corals are not restricted to just reefs, many solitary corals may

be found in rocks where reefs are not present (such as Cyclocyathus

which occurs in the Cretaceous period Gault clay formation of England).

Useful fossils: As well as being important rock builders, some corals are useful

as zone (or index) fossils, enabling geologists to date the age

the rocks in which they are found, particularly those found in the

limestones of the Carboniferous period.

Sensitive to the environment: Coral can be sensitive to environmental changes, and as a result are generally protected through environmental laws. A coral reef can easily be swamped in algae if there are too many nutrients in the water. Coral will also die if the water temperature changes by more than a degree or two beyond its normal range or if the salinity of the water drops. In an early symptom of environmental stress, corals expel their zooxanthellae; without their symbiotic unicellular algae, coral tissues then become colorless as they reveal the white of their calcium carbonate skeletons, an event known as coral bleaching.

Coral reef in danger: Scientists are predicting that over 50% of the coral reefs in the world may be destroyed by the year 2030.

Don't break the coral! Many governments now prohibit removal of coral from reefs to prevent damage by divers taking pieces of coral. However this does not stop damage done by anchors dropped by dive boats or fishermen. In places where local fishing causes reef damage, such as the island of Rodrigues, education schemes have been run to educate the population about reef protection and ecology. Don't break the coral! Many governments now prohibit removal of coral from reefs to prevent damage by divers taking pieces of coral. However this does not stop damage done by anchors dropped by dive boats or fishermen. In places where local fishing causes reef damage, such as the island of Rodrigues, education schemes have been run to educate the population about reef protection and ecology.

Destruction to the reefs: A combination of temperature changes, pollution, and overuse by divers and jewelry producers has led to the destruction of many coral reefs around the world. This has increased the importance of coral biology as a subject of study. Climatic variations, such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), can cause the temperature changes that destroy corals. For example the hydrocoral Millepora boschmai, located on the north shore of Uva Island (named Lazarus Cove), Gulf of Chiriquí, Panamá, survived the 1982-83 ENSO warming event, but during the 1997-98 ENSO all the surviving colonies bleached and died six years later.

Good for tourism, bad for coral: Local economies near major coral reefs benefit from recreatioal scuba diving and snorkelling tourism, however this also has deleterious implications such as removal or accidental destruction of coral. Good for tourism, bad for coral: Local economies near major coral reefs benefit from recreatioal scuba diving and snorkelling tourism, however this also has deleterious implications such as removal or accidental destruction of coral.

Coral rag: Ancient coral reefs on land are often mined for limestone or building blocks ("coral rag"). An example of the former is the quarrying of Portland limestone from the Isle of Portland.

Coral rag is an important local building material in places such as the east African coast.

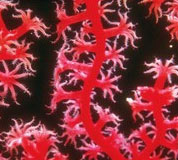

Red coral gemstone: Red shades of coral are sometimes used as a gemstone, especially in Tibet. In vedic astrology, red coral represents Mars. Pure red coral is known as 'fire coral' and it is very rare because of the demand for perfect fire coral for jewellery-making purposes. Red coral gemstone: Red shades of coral are sometimes used as a gemstone, especially in Tibet. In vedic astrology, red coral represents Mars. Pure red coral is known as 'fire coral' and it is very rare because of the demand for perfect fire coral for jewellery-making purposes.

Some coral species exhibit banding in their skeletons resulting from annual variations in their growth rate. In fossil and modern corals these bands allow geologists to construct year-by-year chronologies, a kind of incremental dating, which combined with geochemical analysis of each band, can provide high-resolution records of paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental change.

Certain species of corals form communities called microatolls. The vertical growth of microatolls is limited by average tidal height. By analyzing the various growth morphologies, microatolls can be used as a low resolution record of patterns of sea level change. Fossilized microatolls can also be dated using radioactive carbon dating to obtain a chronology of patterns of sea level change. Such methods have been used to used to reconstruct Holocene sea levels.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License |