|

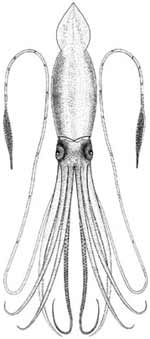

Real giants: They are deep-ocean dwelling squid that can grow to a tremendous

size: recent estimates put the maximum size at 10 m (34 ft) for

males and 13 m (44 ft) for females from caudal fin to the tip of

the two long tentacles (second only to the Colossal Squid at an

estimated 14 m, one of the largest living organisms). The mantle

length, though, is only about 2 m (7 ft) in length (more for females,

less for males), and the length of the squid excluding its tentacles

is about 5 m (16 ft). There were reported claims of specimens of

up to 20 m (66 ft), but none had been scientifically documented. Real giants: They are deep-ocean dwelling squid that can grow to a tremendous

size: recent estimates put the maximum size at 10 m (34 ft) for

males and 13 m (44 ft) for females from caudal fin to the tip of

the two long tentacles (second only to the Colossal Squid at an

estimated 14 m, one of the largest living organisms). The mantle

length, though, is only about 2 m (7 ft) in length (more for females,

less for males), and the length of the squid excluding its tentacles

is about 5 m (16 ft). There were reported claims of specimens of

up to 20 m (66 ft), but none had been scientifically documented.

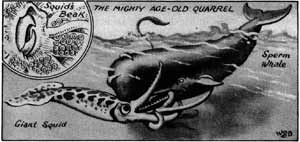

Light giants: Despite their great length, giant squid

are not particularly heavy when compared to their chief predator,

the Sperm Whale, because the majority of their length is taken up

by their eight arms and two tentacles. The weights of recovered

specimens have been measured in hundreds, rather than thousands,

of kilograms. Post-larval juveniles have been discovered in surface

waters off New Zealand, and there are plans to capture more such

juveniles and maintain them in an aquarium in an attempt to learn

more about the creature's biology and habits.

Second largest eyes: Giant squid possess the second largest eyes of any living creature,

over 1 foot (30 cm) in diameter, and their arms are equipped with

hundreds of suction cups in total; each is mounted on an individual

"stalk" and equipped around its circumference with a ring

of sharp teeth to aid the creature in capturing its prey by firmly

attaching itself to it both by suction and perforation. The size

of these suction cups can vary from 2 to 5 cm in diameter (one to

two inches), and it is not uncommon to find their circular scars

on the head area of sperm whales that have fed — or attempted

to feed — upon giant squid. The only other known predator of

the adult giant squid is the Pacific sleeper shark, found off Antarctica,

but it is not yet known whether these sharks actively hunt the squid,

or are simply scavengers of squid carcasses. Because sperm whales

are skilled at locating giant squid, scientists have attempted to

conduct in-depth observations of sperm whales in order to study

squid.

Buoyant and untasty: One of the more unusual aspects of giant squid (as well as some

other species of large squid) is their reliance upon the low density

of ammonia in relation to seawater to maintain neutral buoyancy

in their natural environment, as they lack the gas-filled swim bladder

that fish use for this function; instead, they use ammonia (in the

form of ammonium chloride) in the fluid of their flesh throughout

their bodies, making it taste not unlike salmiakki. This makes the

giant squid unattractive for general human consumption, although

sperm whales seem to be attracted by (or are at least tolerant of)

its taste. Buoyant and untasty: One of the more unusual aspects of giant squid (as well as some

other species of large squid) is their reliance upon the low density

of ammonia in relation to seawater to maintain neutral buoyancy

in their natural environment, as they lack the gas-filled swim bladder

that fish use for this function; instead, they use ammonia (in the

form of ammonium chloride) in the fluid of their flesh throughout

their bodies, making it taste not unlike salmiakki. This makes the

giant squid unattractive for general human consumption, although

sperm whales seem to be attracted by (or are at least tolerant of)

its taste.

Growth rings: Like all cephalopods they use special organs called statocysts

to sense their orientation and motion in the water. The age of giant

squids can be estimated by "growth rings" in the statocyst's

"statolyth" much like counting tree rings. Much of what

is known about these animals come from estimates based on these,

and from undigested beaks found in sperm whale stomachs.

Mysterious mating: The reproductive cycle of the giant squid is still a great mystery,

but what has been learned so far is both bizarre and fascinating;

male giant squid are equipped with a prehensile spermatophore-depositing

tube, or penis, of over 3 feet (90 cm) in length, which extends

from inside the animal's mantle and apparently is used to inject

sperm-containing packets into the female squid's arms — how

exactly the sperm then is transferred to the egg mass is a matter

of much debate, but the recent recovery in Tasmania of a female

specimen having a small subsidiary tendril attached to the base

of each of its eight arms could be a vital clue in the solution

of this enigma. The giant squid lacks the hectocotylus used for

reproduction in many other cephalopods.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License

|