|

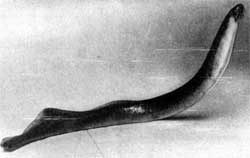

Eel Appearance: Outwardly resembling eels in that they have no scales, an adult lamprey can range anywhere from 5 to 40 inches (13 to 100 centimetres) long. Lampreys have one or two dorsal fins, large eyes, one nostril on the top of their head, and seven gills on each side. Eel Appearance: Outwardly resembling eels in that they have no scales, an adult lamprey can range anywhere from 5 to 40 inches (13 to 100 centimetres) long. Lampreys have one or two dorsal fins, large eyes, one nostril on the top of their head, and seven gills on each side.

Like No Other: The unique morphological characteristics of lampreys, such as their cartilaginous skeleton, means that they are the sister taxon of all living jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) and are not classified within the Vertebrata itself. The hagfish, which superficially resembles the lamprey, is the sister taxon of the lampreys and gnathostomes.

Life on the Beach: Lampreys mostly live in coastal and fresh waters, although at least one species, Geotria australis, probably travels significant distances in the open ocean. They are found in most temperate regions except Africa. Their larvae have a low tolerance for high water temperatures, which is probably the reason that they are not found in the tropics.

Some lampreys are landlocked and remain in fresh water, and some of these stop feeding altogether as soon as they have left the larval stage. The landlocked species are usually rather small.

Super Eel: Recent studies reported in Nature suggest that lampreys have evolved a unique type of immune system with parts that are unrelated to the antibodies found in mammals. They also have a very high tolerance to iron overload, and have evolved biochemical defenses to detoxify this metal.

Life's Purpose: To reproduce, lampreys return to fresh water (if they left it), build a nest, then spawn, that is, lay their eggs or excrete their semen, and then invariably die. In Geotria australis, the time between ceasing to feed at sea and spawning can be up to 18 months long. Life's Purpose: To reproduce, lampreys return to fresh water (if they left it), build a nest, then spawn, that is, lay their eggs or excrete their semen, and then invariably die. In Geotria australis, the time between ceasing to feed at sea and spawning can be up to 18 months long.

Lampreys begin life as burrowing freshwater larvae (ammocoetes). At this stage, they are toothless, have rudimentary eyes, and feed on microorganisms. This larval stage can last five to seven years, and lamprey larva was originally thought to be an independent organism. After these five to seven years, they transform into adults in a metamorphosis which is at least as radical as that seen in amphibians, and which involves a radical rearrangement of internal organs, development of eyes and transformation from a mud-dwelling filter feeder into an efficient swimming predator at sea.

When the lampreys begin their predatory/parasitic lives at sea, they feed by attaching to a fish by their mouths, secreting an anticoagulant to the host, and feeding on its blood and tissue. In most species this phase lasts about 18 months

Frightening Fossils: Lamprey fossils are exceedingly rare: cartilage does not fossilize as readily as bone. Until 2006, the oldest known fossil lampreys were from Early Carboniferous limestones, laid down in marine sediments in North America: Mayomyzon pieckoensis and Hardistiella montanensis. In the 22 June 2006 issue of Nature, Mee-mann Chang and colleagues reported on a fossil lamprey from the same Early Cretaceous lagerstätten that have yielded feathered dinosaurs, in the Yixian Formation of Inner Mongolia. The new species, morphologically similar to Carboniferous and modern forms, was given the name Mesomyzon mengae ("Middle lamprey"). The exceedingly well-preserved fossil showed a well-developed sucking oral disk, a relatively long branchial apparatus showing branchial basket, seven gill pouches, gill arches and even the impressions of gill filaments, as well as about 80 myomeres of its musculature.

Eat Your Lamprey! Lampreys have long been used as food for humans. During the Middle Ages, they were widely eaten by the upper classes throughout Europe, especially during fasting periods, since their taste is much meatier than that of most true fish. King Henry I of England is said to have died from eating "a surfeit of lampreys".

Especially in Southwestern Europe (Portugal, Spain, France) they are still a highly prized delicacy and fetch up to $25 a pound. Overfishing has reduced their number in those parts.

Lamprey Nuisance: On the other hand, lampreys have become a major plague in the North American Great Lakes after artificial canals allowed their entry during the early 20th century. They are considered an invasive species, have no natural enemies in the lakes and prey on many species of commercial value, such as lake trout. Since North American consumers, unlike Europeans, refuse to accept lampreys as food fish, the Great Lakes fishery has been very adversely affected by their invasion. They are now fought mostly in the streams that feed the lakes, with special barriers and poisons called lampricides, which are harmless to most other aquatic species. However those programs are complicated and expensive, and they do not eradicate the lampreys from the lakes but merely keep them in check.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License

|