|

Three Times the Turkey: The two species are the North American Wild Turkey Three Times the Turkey: The two species are the North American Wild Turkey

(M. gallopavo) and the Central American Ocellated Turkey (M. ocellata). The

modern domesticated turkey was developed from

the Wild Turkey.

The Ocellated Turkey was probably also domesticated by the Mayans. It has been speculated that this species is more

tractable than its northern counterpart, and was the source of the present domesticated stock, but there is no morphological

evidence to support this theory.

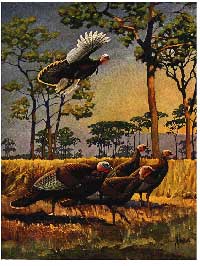

Turkeys are widely hunted, particularly the Wild Turkey in North America. Unlike their domestic counterparts, the turkeys are wary and agile flyers.

The Name Game: When Europeans first encountered these species in the Americas, they incorrectly identified them with the African Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris), also known as the turkey-cock from its importation to Europe through Turkey, and the name of that country stuck as also the name of the American bird. The confusion is also reflected in the scientific name: meleagris is Greek for guinea-fowl.

Choose:

Wild Turkey

Ocellated Turkey

Domesticated Turkey

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

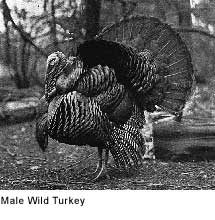

1) Wild Turkey: The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is a gamebird, one of the two species of turkey.

Features: Adults have a small featherless bluish head, a red throat, long reddish-orange legs and a dark body. The head has fleshy growths called caruncles on them, and there is a flap of flesh on the bill called a dewlap that can contract or expand as it is engourged with blood. Males have red waddles on the throat and neck. Each foot has four toes on it, and the males have spurs on the backs of their lower legs.

Plumage: Turkeys have a long dark fan-shaped tail, and their wings are a glossy bronze. Males feathers are also iridescent red, green, copper, bronze and gold. Females feathers are a duller brown and gray color. Parasites can have an effect on the plumage coloration, and the coloration of males could serve as a condition-dependent signal of male health. Plumage: Turkeys have a long dark fan-shaped tail, and their wings are a glossy bronze. Males feathers are also iridescent red, green, copper, bronze and gold. Females feathers are a duller brown and gray color. Parasites can have an effect on the plumage coloration, and the coloration of males could serve as a condition-dependent signal of male health.

The primary wing feathers have white bars. Turkeys have between 5,000-6,000 feathers. All adults have tail feathers that are the same length, whereas the juveniles do not. The males typically have a "beard" made of modified feathers sticking out from the middle of their breast. The beard averages 9 inches long. In some populations, 10-20% of the female turkeys may also have a beard, but it is usually shorter and thinner than the males.

As with many other species of the Galliformes, turkeys exhibit strong sexual dimorphism.

In Flight: They are surprisingly agile fliers and amazingly cunning, unlike their domestic counterparts (see: Domesticated turkey). They are capable of achieving speeds of 50 miles per hour (80 kilometers per hour) in flight but do not fly much higher than tree level nor very far (only up to about .25 mile).

The Gobble: Turkeys make various vocalizations. The different vocalizations of the Wild Turkey are gobbles, clucks, putts, purrs, yelps, cutts, cackles and kee-kees. The male Oscellated Wild Turkey, found in Central/South America, "sings" to announce

his presence.

During the spring breeding season, hens will "yelp" to let the gobbler know her location. Male turkeys, called gobblers or toms, will often gobble announcing their presence.

Turkeys have the ability to make many vocalizations. For instance hens can gobble, which is very uncommon and gobblers can yelp which is actually very common. Immature males called "jakes" tend to "yelp" quite often. The males also emit a very low-pitched drumming sound. The gobble can be heard up to a mile away.

Habitat, Nesting, and Migration:

Open areas like fields are preferred for

feeding, mating, and habitat. The breeding habitat is wooded areas, usually with clearings, across most of the United States and parts of southern Canada, where they are permanent residents. The forested areas keep them hidden from predators. They nest on the ground at the bottom of a tree, shrub or in tall grass. At night, these birds roost in trees. In the United States they will even occasionally wander into backyards seeking out birdseed. Turkeys do not migrate; however, they have been introduced into new habitats across the U.S.

Turkey Dinner: Wild Turkeys are omnivorous, foraging on the ground or climb shrubs and small trees to feed. They prefer eating hard mast such as acorns and nuts of various trees, including hazel, chestnut, and hickory, various seeds, berries, roots and insects. They also eat small vertebrates like snakes, frogs or salamanders. Poults eat insects, berries, and seeds. The turkeys can obtain large populations in small areas because of their ability to forgage for different types of food. Early morning and late afternoon are the desired times for eating.

Play Birds: Males are polygamous, so they form territories that may have as many as 5 hens within. Male wild turkeys display for females by puffing out their feathers, spreading out their tails and dragging their wings. This behavior is most commonly referred to as strutting. Play Birds: Males are polygamous, so they form territories that may have as many as 5 hens within. Male wild turkeys display for females by puffing out their feathers, spreading out their tails and dragging their wings. This behavior is most commonly referred to as strutting.

Their heads and necks are colored brilliantly with red, blue and white. The color can change with the turkeys mood, with a solid white head and neck being the most excited. They also use their gobble noises and make scrapes on the ground for territorial purposes. Courtship begins during the months of March and April, which

is when turkeys are still flocked together in winter areas.

They Court in Pairs: Males are often seen courting in pairs with both inflating their waddles and spreading tail feathers. Only the dominant male would strut and drum on the ground. The average dominant male that courted as part of a pair fathered six more eggs than males that courted alone. Genetic analysis of pairs of males courting together show that they are close relatives with half of their genetic material being identical. The theory behind the team-courtship is that the less dominant male would have a greater chance of passing along genetic material that is identical to his than he would if he was courting alone.

Its an Egg! When mating is finished, females search for nest sites. Nests are shallow dirt depressions engulfed with woody vegetation. Hens lay a clutch of 10-12 eggs, usually one per day. The eggs are incubated for at least 28 days. The poults leave the nest in about 12-24 hours so they are precocial and nidifugous.

Sub-species of Wild Turkey: There are subtle difference in the coloration of the different sub-species of Wild Turkeys. The five sub-species are:

1. Eastern (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris)

Range covers the entire eastern half of the United States; extending also into Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime Provinces in Canada. They number from 5.1 to 5.3 million birds. They were first named forest turkey in 1817, and can grow up to 4 feet tall. The upper tail coverts are tipped with chestnut brown.

2. Osceola or Florida (M. g. osceola) 2. Osceola or Florida (M. g. osceola)

Found only on the Florida peninsula. They number from 80,000 to 100,000 birds. This bird is named for the famous Seminole

Chief Osceola, and was first described in 1980. It is smaller and darker than the Eastern turkey. The wing feathers are very dark with smaller amounts of the white barring seen on other sub-species.

Their overall body feathers are iridescent green-purple color.

3. Rio Grande (M. g. intermedia)

Ranges through Texas to Oklahoma, Kansas, and Colorado, as well as

parts of a few northeastern states. Rio Grande turkeys were also introduced to Hawaii in the late 1950's. They number from 1,022,700 to 1,025,700 birds. This sub-species is native to the central plain states. They were first described in 1879, and have disproportionately long legs. Their body feathers often have a green-coppery sheen to them. The tips of the tail and lowrer back feathers are a buff-very light tan color. Habitats are brush areas next to streams, rivers or mesquite pine and scrub oak forests. Only turkey to be found up to 6,000 feet in elevation and are gregarious.

4. Merriam's (M. g. merriami)

Ranges through the Rocky Mountains and the neighboring prairies of Wyoming, Montana and South Dakota. They number from 334,460 to 344,460 birds. Live in ponderosa pine and mountain regions. Named in 1900 in honor of C. Hart Merriam, the first chief of the US Biological Survey. The tail and lower back back feather s have white tips. They have purple and bronze reflections.

5. Gould's (M. g. mexicana)

Native to central Mexico and the southern-most parts of Arizona and New Mexico. They number from 650 to 800 birds. Heavily protected and regulated. First described in 1856. They exist in small numbers but are abundant in Northwestern portions of Mexico. Gould's are the largest of the five sub-species. They have longer legs, larger feet, and longer tail feathers. The main color of the body feathers are copper and greenish-gold.

Turkey Trivia:

The idea that Bejamin Franklin preferred the Turkey as the national bird comes from a letter he wrote to his daughter in 1784 criticizing the choice of the Eagle as the national bird and suggesting that a Turkey would have made a better alternative.

The wild turkey has been adopted as the official game bird of South Carolina, Alabama, Oklahoma and Massachusetts.

Turkey is a popular main dish for the Thanksgiving holiday, which is held in November in the United States and October in Canada. The Aztecs domesticated the southern Mexican sub-species, M. g. mexicana

Turkeys in Danger: The range and numbers of the Wild Turkey had decreased at the beginning of the 20th century due to hunting and loss of habitat. Game managers estimate that the entire populations of Wild Turkeys in the U.S.A was as low as 30,000 in the early 1900's. Game officials made efforts to protect and encourage the breeding of the surviving wild population. As the Wild Turkey's numbers rebounded in the 1980s and 1990s, hunting was legalized in 49 US states, excluding Alaska. Current estimates place the entire Wild Turkey population at 7 million individuals. In recent years, trap and transfer projects have reintroduced Wild Turkeys to several provinces of Canada as well.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2) Ocellated Turkey: The Ocellated Turkey exists only in a 50,000 square mile area comprised of the Yucatán Peninsula range includes the states of Quintana Roo, Campeche and Yucatan, as well as parts of southern Tabasco and northeastern Chiapas.

Beautiful Birds: The body feathers of both sexes are a mixture of bronze and green iridescent color. Although females can

be duller with more green, the breast feathers do not generally differ and can not be Beautiful Birds: The body feathers of both sexes are a mixture of bronze and green iridescent color. Although females can

be duller with more green, the breast feathers do not generally differ and can not be

used to determine sex. Neither sex have beards. Tail feathers of both sexes are bluish-grey with an eye-shaped, blue-bronze spot near the end with a bright gold tip.

The spots, for which the Ocellated is named, lead some scientists to believe that the bird is more related to peafowl than to Wild Turkeys. The upper, major secondary wing coverts are rich iridescent copper.

The primary and secondary wing feathers have similar barring to that of North American turkeys, but the secondaries have more white, especially around the edges.

Features: Both sexes have blue heads with some orange or red nodules, which are more pronounced on males. The males also have a fleshy blue crown covered with nodules, similar to those on the neck, behind the snood. During breeding season this crown swells up and becomes brighter and more pronounced in its yellow-orange color. The eye is surrounded by a ring of bright red skin, which is most visible on males during breeding season. The legs are deep red and are shorter and thinner than on North American turkeys. Males over one year old have spurs on the legs that average 1.5 inches, which lengths of over 2 inches being recorded. These spurs are much longer and thinner than on North American turkeys.

Size: Ocellated Turkeys are much smaller than any of the subspecies of North American Wild Turkey, with adult hens weighing in at about 8 pounds before laying eggs and 6-7 pounds the rest of the year, and adult males weighing about 11-12 pounds during breeding season.

Running and Roosting: Turkeys spend most Running and Roosting: Turkeys spend most

of the time on the ground and often prefer to run to escape danger through the day rather than fly, though they can fly swiftly and powerfully for short distances as the majority of birds in this order do in necessity. Roosting is usually high in trees away from night hunting predators such as Jaguars and usually in a family group.

Voice: The voice is similar to the northern species too, the male making the "gobbling" sound during the breeding season, while

the female bird makes a "clucking" sound.

Nest and Nestlings: Female Ocellated Turkeys lay 8-15 eggs in a well concealed nest on the ground. She incubates the

eggs for 28 days. The young are precocial and able to leave the nest after one night. They then follow their mother until they reach young adulthood when they begin to range though often re-grouping to roost.

In the past, it has sometimes been treated in a genus of its own, as Agriocharis ocellata, but the differences between this species and Meleagris gallopavo are too small to justify generic segregation.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3) Domesticated Turkey: 3) Domesticated Turkey:

Just the Facts: The domesticated turkey is a large poultry

bird raised for food. The modern domesticated turkey descends from the wild turkey, one of the two species of turkey (genus Meleagris); however, the ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata,) was also domesticated. Despite the name, turkeys have no relation to the country

of Turkey and are instead native

to North America.

The turkey is reared throughout temperate

parts of the World, and is a popular form of poultry, partially because industrialised

farming has made it very cheap for the amount of meat it produces. The female domesticated turkey is referred to as a hen and the chick as a poult. In the United States, the male is referred to as a tom, while in Europe, the male is a stag.

History of Domestic Turkey Turkeys were brought back to Europe shortly after their discovery in the New World. For this reason, many distinct turkey breeds were developed in Europe due to cross breeding. (e.g. Spanish Black, Royal Palm). Turkey was one of the many game species hunted by early American colonists and is traditionally (though not in actuality) thought to have been served at the first Thanksgiving. Turkeys have been a staple on farms since their discovery in colonial times. In the midwestern United States in the mid to late 1800s, domestic turkeys were actually herded across the range in a manner similar to herding cattle. In the early 20th century, many advances were made in the breeding of turkeys resulting in varieties such as the Beltsville Small White.

Plumage: The great majority of domesticated turkeys have white feathers, although brown or bronze-feathered varieties are also raised.

Domestic Differences: Modern animal husbandry has resulted in significant differences between wild turkeys and commercial farm animals. Broad-breasted varieties are prized for their white meat, fast growth, and excellent feed-conversion ratios. Broad-breasted varieties are typically produced by artificial insemination to avoid injury of the hens by the much larger toms. Modern commercial varieties

have also lost much of their natural ability to forage for food and to escape predators. For this reason, many non-commercial hobbyists as well as organic farmers grow "heritage" breeds such as the Royal Palm or Naragansett -- varieties traditionally grown on farms prior to the advent of large-scale agriculture.

Fatherless Child: Some commercial turkey hens occasionally produce young from unfertilized eggs in a process called parthenogenesis.

Origins: Suggestions have been made that the Mexican Ocellated Turkey (Meleagris ocellata) might also be involved, but the plumage of domestic turkeys does not

support this theory; in particular, the chest tuft of domestic turkeys is a clear indicator of descent from the Wild Turkey (the Ocellated Turkey does not have this tuft).

Commercial Production: Prior to World War II, turkey was something of a luxury in Britain, with goose or beef a more common Christmas dinner (In Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol Bob Cratchit had a goose before Scrooge bought him a turkey). Commercial Production: Prior to World War II, turkey was something of a luxury in Britain, with goose or beef a more common Christmas dinner (In Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol Bob Cratchit had a goose before Scrooge bought him a turkey).

Intensive farming of turkeys from the late 1940s, however, dramatically cut

the price and it became far and away the most common Christmas dinner meat. With the availability of refrigeration, whole turkeys could be shipped frozen to distant markets.

Later advances in control of disease increased production even more. Advances in shipping, changing consumer preferences and the proliferation of commercial poultry plants for butchering animals has made fresh turkey available to the consumer.

Uses of Feathers: Approximately two to four billion pounds of poultry feathers are produced every year by the poultry producing industry. Most of the feathers are usually ground up and used as filler for animal feed. Researchers at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have patented a method of removing the stiff quill from the fibers which make up the feather. As this a potential untapped supply of natural fibers, research has been conducted at Philadelphia University to determine textile applications for feather fibers. To date, turkey feather fibers have been blended with nylon and spun into yarn which was then used for knitting. The yarns were tested for strength while the fabrics were evaluated as potential insulation materials. In the case of the yarns, as the percentage of turkey feather fibers increased the strength decreased. In fabric form, as the percentage of turkey feather fibers increased the heat retention capability of the fabric increased.

To Kill a Turkey: To kill a live turkey, withhold food for a day to help ensure the digestive system is empty. (Some recommend also feeding the turkey hard liquor before slaughter, both to sedate it and perhaps as a way of flavoring the meat.) Putting the turkey in a bag, with one corner cut out for the head, helps keep the turkey from thrashing and damaging itself or the people involved in preparing it. To Kill a Turkey: To kill a live turkey, withhold food for a day to help ensure the digestive system is empty. (Some recommend also feeding the turkey hard liquor before slaughter, both to sedate it and perhaps as a way of flavoring the meat.) Putting the turkey in a bag, with one corner cut out for the head, helps keep the turkey from thrashing and damaging itself or the people involved in preparing it.

One method is to hammer two nails into a stump and bend them, then put the turkey's head on the stump and turn the nails to hold the turkey's head still, then remove the turkey's head with an axe. The turkey will thrash for a few moments. More commonly, a turkey is placed upside down inside a metal cone manufactured for this purpose, its neck is cut, and the blood is allowed to drain out.

To Clean A Turkey: Hang it upside down to bleed for a half hour or so. Then pluck it. Smaller feathers can be pulled off in a bunch; larger feathers need to be removed

one at a time so as not to tear the skin. Stubborn feathers can be pulled with pliers or a forceps. When all the feathers are removed, rinse the turkey's anus to remove any residue, then insert a sharp knife just below the hip bone, but not so deep as to puncture any of the internal organs.

Butchering: Cut down and around on either side of the anus, making sure it's angled up to keep any excretion off the meat. Carefully pull out and discard. Then reach inside the turkey and remove all organs, as well as large globs of fat. If desired, the heart, liver (slice away from other innards, being careful not to puncture the green gall), and gizzard can be saved for giblets. If the gizzard is saved, slice it in half until the gravel inside grates against the knife, then slice around and open up, peeling away the inner layer and discarding the contents. After all the organs have been removed, turn the turkey around and cut around the circumference of the neck and peel down, exposing the esophogus and windpipe. For each, separate them from their attachment points and pull them out, including the crop in the case of the esophogus. Rinse the turkey out with cold water and, if desired, hang and chill for a day or so before freezing.

Turkey Traditions: Turkeys are traditionally eaten as the main course of large feasts at Christmas in Europe and North America, as well as Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada, in both cases having displaced the traditional goose. While eating turkey was once mainly restricted to special occasions such as these, turkey is now eaten year round and forms a regular part of many diets. Turkey Traditions: Turkeys are traditionally eaten as the main course of large feasts at Christmas in Europe and North America, as well as Thanksgiving in the United States and Canada, in both cases having displaced the traditional goose. While eating turkey was once mainly restricted to special occasions such as these, turkey is now eaten year round and forms a regular part of many diets.

Turkey Preparations: In countries where turkey is popular, it is available commonly in supermarkets. Turkeys are sold sliced and ground, as well as "whole" in a manner similar to chicken with the head, feet, and feathers removed. Frozen whole turkeys remain popular. Sliced turkey is frequently used as a sandwich meat or served as cold cuts. Ground turkey is sold just as ground beef, and is frequently marketed as a healthy beef substitute. Without proper preparation, turkey is usually considered to end up less moist than, say, chicken or duck. Leftovers from roast turkey are generally served as cold cuts on Boxing Day.

Wild Turkey Meat: Wild turkeys, while technically the same species as domesticated turkeys, have a very different taste from farm-raised turkeys. Almost all of the meat is "dark" (even the breasts) with a more intense turkey flavor. Older heritage breeds also differ in flavor.

Health concerns: Turkey is generally considered healthier and less fattening than red meat. Turkey is high in tryptophan, and is commonly credited with causing sleepiness after a meal, however this is largely a misconception. Turkey dinners are commonly large meals served with carbohydrates, fats, and alcohol in a relaxed atmosphere, all of which are bigger contributors to post-meal sleepiness than the tryptophan in turkey.

This section is a stub. You can help by adding to it.

Turkeys in culture: Norman Rockwell featured a roast turkey as a symbol of prosperity in his painting "Freedom from Want", one of his Four Freedom Series.

Turkey dung for fuel: Turkey droppings are planned to fuel an electric power plant in western Minnesota. The plant will provide 55 megawatts of power using 700,000 tons of dung per year. Plant will begin operating in 2007. Three such plants are in operation in England.

All text is available under the terms

of the GNU Free Documentation License |